This was my final paper for my Usability Studies class last semester. Because I had never had the opportunity to conduct or take part in an actual usability study, I decided to stick with what I knew. I’d been singing a lot of choral music at the time, and my colleagues and I were getting frustrated at the irksome little choices some of the publishers had made. I don’t think this paper will change the industry, but it’s been interesting hearing feedback from non-musicians who had never considered this realm of usability.

P.S. I got an A. 🙂

———————————————————-

Usability in Sheet Music

Amanda M. White

Submitted to Dr. David Hailey

Utah State University December 9, 2011

Imagine being surrounded by glorious music. Heavenly voices surround you on all sides, powerful, beautiful, lifted up in song. An inspired song, praising a benevolent being and moving to all who hear it.

Suddenly, in a heartbeat, the music turns sour. The harmonies crash into rough and uneven dissonances, clashing, until finally the voices tumble away into silence.

“Sorry,” a soprano pipes up. “Bad page turn.”

As a professional choral singer of fourteen years, this happens in rehearsal about once a month. In musicians’ jargon it is commonly called “train wreck,” or more gently, a “derailment.” Either way, the imagery is clear: we move forward, over hills and valleys, through tunnels and over bridges, until suddenly we are thrown off course and are unable to continue. This is understandable to even non-musicians. Music is hard, mistakes happen, we move on. But what non-musicians might not realize is that these mistakes are often caused not by difficulty in the music, but by the way it is published. Careless edits or space-saving shortcuts taken by music publishers, who might never view the final product—not the published manuscript, but the performance of the music—cause tangible setbacks to musicians trying to do their jobs.

In this paper, I’m going to examine some of the common problems caused by music publishing. I have chosen to focus on choral music, because it is one of the forms of written music (along with piano accompaniments) most likely to be sight-read.

What is sight-reading?

Sight-reading means that a musician, or a group of musicians, plays or sings an unfamiliar piece of music, without preparation, as written. It is to be distinguished from gradual forms of music learning, such as playing a two-handed piece one hand at a time, singing a piece on solfège or numeric syllables, learning the rhythm separately from the melodies and harmonies, or picking through a piece of music slowly and with starts and stops. To sight-read a piece of music means to pick it up, never having seen it before, and instantly perform it as close to perfectly as possible. It is akin to an actor doing a “cold reading,” picking up a script and reading one of the roles in a scene, without having studied or memorized the lines (sometimes without any background information on the character or plot). As one would surmise, it is a highly efficient rehearsal method, but requires excellent musicianship skills.

When singers work this way, the skill is more accurately known as “sight-singing,” although the term “sight-reading” is still more often used in the vernacular. Sight-singing has its own skill requirements apart from most instrumental reading. The absence, practically speaking, of a visible or tactile means of pitch selection means that singers must choose their tones mentally, rather than physically. A pianist, for example, who wants to play a B natural above middle C, can simply look at the piano and press the correct button. A singer has no “button” to look at or press, so they must either have perfect pitch (the vast majority do not), or mentally calculate what tone to sing by its relationship to notes preceding it. Additionally, sight-singing almost always involves reading text and music at the same time.

This is not to say that sight-singing is harder than instrumental sight-reading, as other instruments have inherent difficulties. Some instruments, such as pianos and harps, have to play many notes simultaneously; singers, while making use of the other lines of music, are only responsible for correctly singing one pitch at a time. Additionally, due to physical limitations, the addition of text, and the necessity of breathing (a handicap shared with wind instruments), vocal parts are usually less rhythmically complex than their instrumental counterparts. Rather, this is to point out particular problems sight-singers must face, as these will come up as we examine usability issues.

Lyrics not printed below each staff

The vast majority of choral music is sung with text, in English or another language (usually Latin or German in choral music). So not only does the singer have to accurately sing the notes and rhythms (with good technique), she must also accurately sing the correct words (with good diction). There are several inhibitors of this ability, the oddest being the occasional absence of text from below some of the vocal lines.

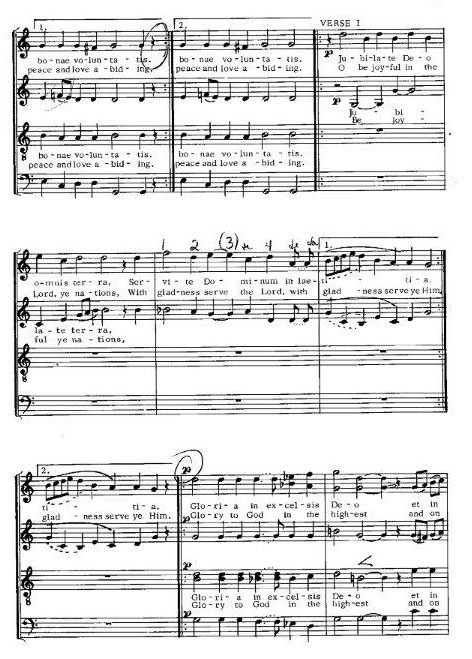

In Figure 1, the Latin and English text is printed only below the soprano and tenor lines during the refrain. The altos and basses are expected to look above their lines for the text. During the verse, things become even more confusing. The alto line begins with lyrics, which then disappear mid-system. This is not a random occurrence; it has a logical reason, although I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a valid one. The two measures of alto text are printed because the altos are at that point singing such a different rhythm from the sopranos that their syllables do not fall on the same beats. For example, the sopranos are already to the “-te” of Jubilate, the fourth syllable, when the altos arrive at “-bi-,” the second syllable. In fact, the text between the two parts is not equal. The alto line skips two words, “Deo” and “omnis,” changing the translation from “Praise God all earth” to “Praise earth.” Scriptural integrity aside, it is clear that this setting necessitates texts printed for the individual lines. However, I would argue that the text should be printed for the individual lines throughout the score.

In Western music tradition, text is always placed below the music, with rare exception. It is as ingrained in a singer’s mind as a green light meaning “go.” This is true of opera, musical theater, and even sheet music for pop and rock songs. This is largely tradition, but it is also because the space above the line is needed for dynamic, tempo, and other musical markings. You can see “VERSE 1” printed above the first system of Figure 1, as well as “p” (piano) printed above the last system. (The piano marking is placed below the system at Verse 1, presumably because the space above the line was taken by the words “VERSE 1.”) While there is little chance of a singer mistakenly intoning “Verse 1” to the tune instead of “Jubilate Deo,” there could be more risk with longer notes, especially those written in the same language as the text. While I have yet to hear a singer accidentally sing “Flowing, with freedom” instead of the intended text, my point is that there is a reason for the template. Breaking from this template is a distraction that can cause errors.

In this particular edition, the deletion of the alto and bass lines is doubly problematic because of the bilingual text. The English printed below the Latin (in the same font and with no other distinction, a usability issue unto itself) means that when an alto or a bass looks to the top line for the text, their eyes will land on the English first. Pieces such as this are almost never done in translation (especially not if the original is such a universal singing language as Latin), so the edition would have been better off not including it at all. But since they did, it makes their decision to only include text on every other staff that much more problematic.

I’d like to invite the reader to examine, even measure, the spacing between the staffs in each system. The space between the soprano and alto staffs, the alto and tenor staffs, and the tenor and bass staffs, are all equal. The publishers are saving no space by leaving out the text between the alto and tenor lines, and there is clearly plenty of space below the bass line. The only gain is the extra white space, which in this case is not having any positive effect. It is not more “calming” and “clean” to look at when your eyes have to scramble to find the lyrics.

No measure numbers

The above score features a secondary problem: The measures are not numbered. Most choral scores will number the measures of each movement. If not every measure, usually at least one per line, or a few per page, are numbered, and the musicians can count forward or backwards from there to determine the number of the specific measure they want to call attention to. Either alternately or in addition to measure numbers, rehearsal letters or numbers can be included. This is especially common in larger works. Important landmarks in the piece are labeled, so that a conductor can say “Tenors, can I hear you at letter F?” Measure numbers, however, are much more useful, as they occur more frequently and allow for greater specificity. It’s easier for a conductor to count backwards from twenty-two and say “Go to measure nineteen,” then it is to say, “seventeen measures after B.”

This score contains no measure numbers whatsoever. It has occasional rehearsal letters, but only some are included in the vocal part score. Since the conductor’s score, containing all the vocal and instrumental parts, is laid out drastically differently than the vocal part scores, it is hard for the conductor and singers to communicate to each other about where in the song they are. The conductor will say something like, “Two before A,” but the singers don’t have “A,” so they don’t know where that is. The singers will say “Second measure, top of page two,” but the conductor’s page numbers are different. Problems like this are time-consuming, and easily preventable. It takes little space or ink to add tiny numbers to every few measures. In no circumstances should this sort of score be published without measure numbers, especially if rehearsal letters are not consistently included.

Dynamic markings only in the accompaniment

A related problem to the above is a score that might have all the lyrics in the correct places, but reserves the dynamics, tempo markings, and other notes for the accompaniment. With the singers busy reading their own lines, the only person who sees these markings is the pianist (if there is one), conductor, and possibly the basses, since their lines are in proximity.

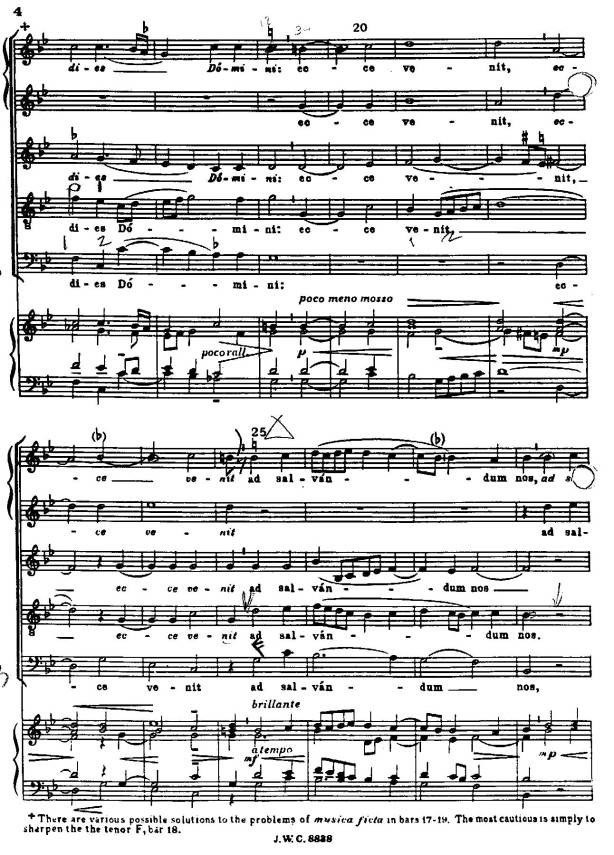

In figure 2, you’ll notice all manner of markings in the accompaniment. Starting with “poco rall.” (“slow down a little”) and a decrescendo (get gradually quieter) in measure 18, you will see dynamic markings (p, mp), tempo markings (poco meno mosso, a tempo), crescendi and decrescendi both independently and as hairpins (crescendo then immediately decrescendo), tenuto markings, and even a stylistic order, “brillante.” If you look up at the vocal parts, exactly none of these markings are included. The cherry on top is that this is an a capella piece. The “accompaniment” is not meant to be played, and is only a reduction of the above voicings for a pianist to play at rehearsals.

It can be argued that this piece, dated 1572, is from a time period where dynamics were not normally included, which means that the markings in the accompaniment are editorial, and thus only “suggestions.” However, I would argue that the publisher should make up their minds as to whether to include them, and stick to that decision. The score can be published with no markings, as most choirs and directors are capable of making their own artistic choices; or it can be published with them. To include them in only the piano part serves no one, especially when there is not actually a piano being played.

Half notes that look like quarter notes

Figure 2 also features another problem: half notes (which have empty circles) that are printed too small and with too thick a font, making them look like quarter notes (which have filled-in circles). Is is apparent from the singers’ pencil markings in the score that many people struggled with this problem. Some dealt with it by drawing empty circles near the note, such as in measures twenty-two and twenty-eight. A tenor in measure seventeen has sketched a half note above his pitch. Less legible (in this reproduction and in the original) are those who tried to draw an empty circle over the half note, such as the soprano in measure nineteen. Another soprano in the same spot tried to correct the problem by writing “1 2” and “3 4” over the two half notes, to remind herself that each note is worth two beats (half note), not one (quarter note). Most telling, a soprano at some point actually believed that the half note in measure twenty-five was a quarter note, thus causing a measure of 3/4 instead of 4/4 like the others. This is evidenced by the triangle written over measure twenty-five, which is a symbol for 3/4. Hopefully, she realized her misunderstanding by the time of the performance.

Tenor line in bass clef

(Sorry, due to weirdness, the above image came out smaller than it originally was in my paper.)

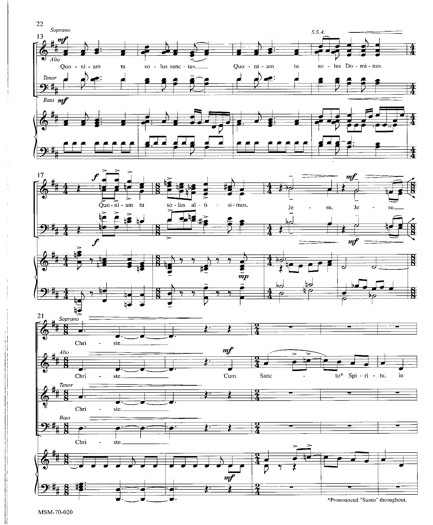

Most people, musicians or not, had at least enough music education in school to know that there is a treble clef and a bass clef. (There are other clefs as well, but these are the most common, and the only ones singers deal with.) Sopranos, altos, and tenors usually sing in treble clef (the tenors an octave below), and basses and baritones (for the purposes of choral music, baritones are considered “first basses”) sing in bass clef. This applies to both choral and solo music. When you look at a four-staff choral score, you will see three lines of treble clef (the tenor one may or may not have a tiny “8” at the bottom to indicate the octave below, but if not, it’s implied), and one line of bass clef.

However, when you look at a two-staff choral score, you’ll see something quite different (first two systems of Figure 3). The soprano and alto voices are placed on a single staff, and the tenor and bass voices are placed on another. The soprano and alto voices are notated in treble clef, while the tenor and bass voices are notated in bass clef. Everything is fine here, except for the tenors. They do not usually sing in bass clef, and can get thrown off by the transposition, especially when a score toggles between two- and four- staff notation.

So why not have tenors learn bass clef in the first place, instead of treble clef? Tenor writing is really too high for bass clef. In two-staff notation, the tenor line often sits very high on the staff, with several ledger lines often necessary. As any coloratura soprano or flautist can tell you, the farther off the staff you get, the more brainpower it takes to recognize the note. Resisting the urge to comment on the amount of brainpower available to tenors, bass clef is simply not conducive to tenor music.

Essentially, reducing a choral score to two scores is “pianist think.” A pianist thinks in terms of what their two hands can play: two top voices in one hand, two bottom voices in the other. Though much of the time, the tenor part is closer in range to the alto than to the bass. But I think this sort of editing happens when choral scores are arranged by pianists, rather than by singers. Which makes sense: many, possibly most, composers and conductors are also pianists (and/or organists). While most know the basics of singing technique, few are highly-trained singers. So it’s easy to see why scores end up being published this way: it makes sense to the people writing and conducting the music, and is an efficient use of space. However, the mistakes it can lead to are not an efficient use of rehearsal time. Two-staff notation should be reserved for only the simplest music.

Changing number of staffs

In the third system of Figure 3, you’ll notice a drastic change in the way the score looks. Here, the layout has gone from two vocal staffs to four, solving our tenor problem. However, this change causes more difficulties than it solves.

The sudden shift in layout throws a singer’s eye tracking off-base. An alto who was singing the top line is suddenly on the second line. A tenor who was on the bottom line is now on the third line. It sometimes takes singers a measure or two to figure out what has happened, during which time they are singing the wrong part.

The tenor problem is even worse here, because the tenors are not only adjusting their eye tracking to a new line, but adjusting to a new clef. They have been singing in bass clef, and are suddenly in treble clef. A tenor who catches the change in staffs, but does not adjust for the change in clef, will try to make a sudden skip down to a C# (what the pitch would be in bass clef), instead of continuing up to an A (what the pitch is in treble clef).

This sort of switch is not only a problem on the page where it happens, but on subsequent pages. Every time a singer reaches a new page, they have to find their line again. This is normally easy, and done on an unconscious level. However, if the systems are changing back and forth from two to four staffs, it is easy for a singer to forget which line they are supposed to be on, and to sing the wrong line. This is not a problem for sopranos, who always sing the top line, or basses, who always sing the bottom line, but rather for the middle voices, the altos and tenors.

Fortunately, this score includes a note of redemption in the “warning” marks for the staff expansion. At the end of measure 20, before the staffs expand into four, there are “up/down” arrows, informing the singers to expect an expansion. While these small markings are easy to miss, they are better than an unprepared change, and will often reduce mistakes made. When expanding or reducing staff lines, it is very important to include this kind of signal.

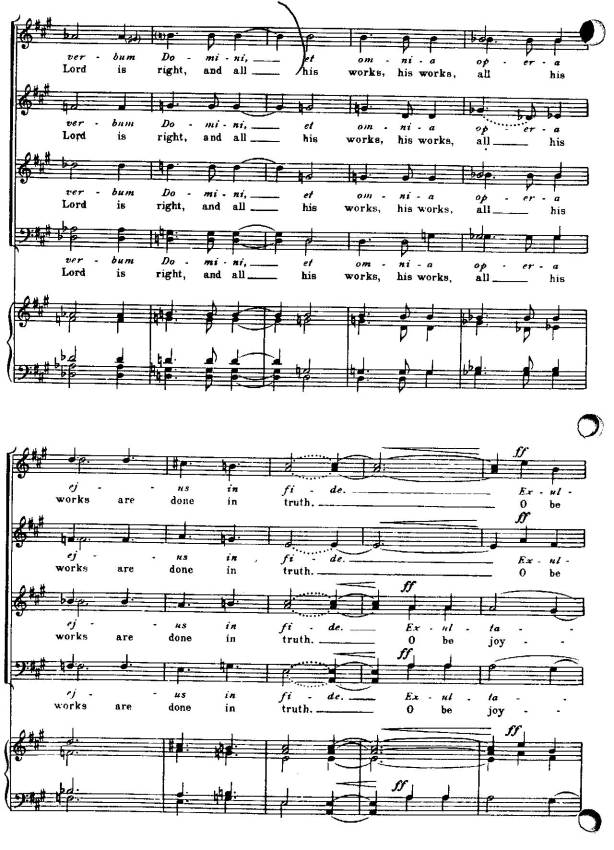

Bilingual editions with conflicting note values

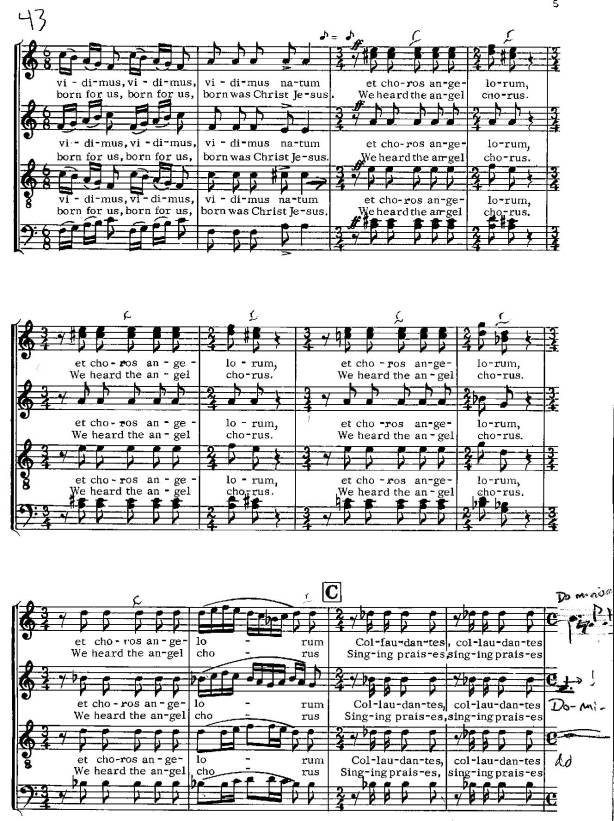

Classical music is an international art, and the texts set to music stem from many different languages. As most singers and audiences are not multi-lingual, publishers often try to reach a wider audience by including “singing” translations—that is, not word-for- word literal translations, which might not line up syllabically with the music, but a paraphrase of the text that fits the poetic meter of the original. Although contemporary practice usually encourages singing in the original language, there are exceptions. Singers in amateur choirs may not be familiar with pronunciation of foreign languages. The director (or, in the case of liturgical music, clergy) may be concerned with the audience understanding the text, especially in cases where program notes (with translations) are not distributed. Languages outside the standard “singing languages” of English, Italian, French, German, and Latin, may be too challenging for even professional singers, so pieces in Russian or Czech are often done in English translation. Generally, though, performing pieces in translation is a dying practice, and the English below the original usually goes ignored.

Singing translations would be a harmless inclusion, except when the translated text does not perfectly fit the rhythm of the original. This leads to different rhythms superimposed on the same staff, as seen in figure 4. This causes many rhythmic and textual errors to singers who are suddenly confronted with two different rhythms in the same measure. When confronted with the first measure of the bottom system of figure 4, singers are likely to make one of three mistakes: re-attacking the Latin syllable (“eee- eee-jus”), predicting the end of the word (this is a commonly sung text and singers are usually familiar with the words it contains) and jumping to the syllable “-jus” half a measure early, or dropping down to the syllable below the note and mistakenly switching into English before they realize what is happening (“ee– are done…”).

While most usability issues can be smoothed over by singers’ penciled-in notations, having extra notes in your measures is difficult to remedy. Scratching them out or trying to circle the proper note just adds clutter to the page. With this in mind, singing translations should only be included when they mimic the rhythm and meter of the original exactly, if they are included at all. (Exceptions can be made for choruses in full operas, which are often performed in the vernacular for theatrical reasons.)

What makes a “bad” page turn?

The most common complaint about printed music is the elusive “bad” page turn. Loosely, this means that a page turn occurs in a place that causes singers to make mistakes. But what exactly makes one page turn worse than another?

To put it in very general terms, a page turn becomes problematic when it immediately precedes something unexpected, that must be dealt with instantly. The fabric of music is patterns, lending an unconscious air of predictability that makes sight-reading possible. Melodic and rhythmic themes repeat, harmonies change and stabilize with certain regularity, time and key signatures are the norm. Of course if everything that happened were predictable, music would be boring. Hence the “surprises” that occur in our scores.

When these surprises occur over a page turn, we don’t have time to mentally prepare for them. The more drastic the change, the more likely mistakes are to occur.

(Page break)

Figure 5 is a good example of a page turn problem, as evidenced by the notations written in by the singers, at least three of which felt the need to actually write in their upcoming notes. This disconnect occurred for them because the notes that begin the next page represent a drastic change from what had gone on in the piece thus far. The rhythm changes from fast and syncopated to slower and on the beat, and the chords are effectively unrelated. The melody also features relatively significant leaps for the first sopranos, altos, and first tenors.

There is no simple solution for this. The only thing publishers can do is be aware of where the challenging changes are. And they are not always the same for every voice part. Sometimes the tenors might have a difficult page turn while the rest of the choir is silent. But if the problem spots can be located, an attempt should be made to not let them land directly on a page turn. Even one measure of buffer is enough to help.

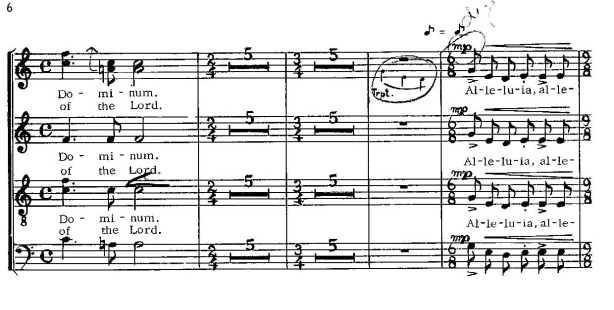

Counting blank measures

The second measure of page six contains a figure that most singers are not used to seeing. The “5” over the horizontal bar means “five measures,” i.e., “five measures of rest.” So in the example above the singers are expected to count five measures of 2/4, then five measures of 3/4, and then one last measure of 3/4 for which a trumpet cue is given.

This method of short hand is the norm for orchestral instrumentalists, who often rest for long stretches of time in between entrances, and do not typically include any sort of accompaniment. It is very rare for singers, however, who typically have an accompaniment in their scores, whether it is a piano or organ part, or a piano reduction for a capella pieces. (Rarely do singers perform from full scores, i.e. “conductor scores,” which would be too heavy to comfortably hold and involve too many page turns. Chamber music is sometimes an exception.) Singers are quite unaccustomed to counting blindly in this fashion. Rather, they are accustomed to following along in the accompaniment, or other voice parts, while they are resting.

Most of the time, the biggest problem is that singers who don’t have perfect pitch need to find their entrance note based on what is happening before their entrance This score, though, redeems itself by including the trumpet cue before the entrance, from which the singers can find their pitches. Still, the problem remains that singers are just not used to counting music in this way. This is evidence to some orchestra members that singers are not as intelligent as they are, or are lacking in musicianship skills. In actuality, it is simply a matter of practice. Singers are so rarely asked to view music in this way, that doing so is disconcerting for them, and leads to confusion over their entrances.

This type of notation should generally be avoided. When it does occur, however, publishers should be extremely generous in the giving of instrumental cues. One measure of “warning” is not enough for many singers to orient themselves.

Are usability issues really to blame?

Singers are usually not as good at sight-reading music as classical instrumentalists, and when rehearsal times are short, mistakes are easy to come by. Are we using “bad page turns” as excuses for mistakes that are our own responsibility? To what extent are usability issues really to blame?

Usability issues don’t cause mistakes single-handedly. Simple music can be read despite most of the above problems, and more skilled readers can often avoid being tripped up by publishing pitfalls. The problems occur when bad publication practices collide with difficult passages of music.

For example, a quick change from four-staff to two-staff notation is perfectly manageable when the music is slow and simple, the singer already has an idea of where the music is going, and there are no other distractions. On the other hand, when sixteenth notes are flying by at rapid speed, tonalities are changing every other measure, and rhythms are surprising, a seemingly minor issue can stop the rehearsal.

Problems can also be compounded. A single usability problem might only trip up one or two people, but combined, they can cause musical train wrecks. Bilingual scores with conflicting note values are already challenging, but if it is also difficult to distinguish half notes from quarter notes, rhythmic accuracy becomes slippery.

What can be done?

Usability problems exist in printed music partly because of carelessness on the part of the publishers, and partly for convenience and cost-cutting measures. Two-staff writing is done because it saves paper. Omitting measure numbers is just laziness.

How much say does the consumer have in this? Unfortunately, not much. Directors choose pieces for the music, the text, or the composer. With the possible exception of anthologies, the publishing practices are rarely a consideration at all. Most pieces are only published by one company, so whoever wants to perform that piece pretty much has to put up with these minor issues.

More power, on the other hand, is in the hands of the composer. Composers with enough “clout” to shop their pieces around to different publishers can consider how well the company ranks in terms of usability. In fact, I find that it’s usually the composers who are most vocal in complaining about these issues. Although they may find that their sway in how their music is printed is limited, it is still more than that of the consumer.

Another option, one that is frequently performed, is for choirs to purchase the music, but operate from self-edited, photocopied versions. A conductor or his assistant can take the time to create a “master copy” from a published edition, adding in measure numbers and missing dynamics, whiting out text in the unused language, writing in missing lyrics, and rearranging the pagination to avoid problematic page turns. According to the Music Publishers Association Copyright Resource Center, this falls under legal copywriting: “Printed copies which have been purchased may be edited OR simplified provided that the fundamental character of the work is not distorted or the lyrics, if any, altered or lyrics added if none exist” (Copying Under Copyright). Presumably, this does not prohibit copying in the intended lyrics when they are omitted from a line of music.

Usability issues are often overlooked by publishers, who are not the ones who have to use the music. Meanwhile, they are interrupting rehearsals, thereby costing organizations money and interfering with our ability to make good music. Although it is not a simple situation for musicians to vote with their dollars, we can still make their opinions known to publishing companies. Other than that, I believe that the bulk of the work will fall to the composers, with the rest of us relegated to editing the scores we want to use ourselves. It is my hope that this paper will help us as musicians to consolidate some of our ideas about what we want and don’t want in printed music, and thus to make it easier for us to vocalize our collective preferences to publishing houses, as consumers, as composers, and as fellow music lovers.

References

Copying Under Copyright: A Practical Guide. (2004-2011.) Retrieved December 9, 2011 from http://www.mpa.org/copyright_resource_center/copying

da Palestrina, G. P. (Composer). (1964). Canite Tuba [Sheet music]. London: Chester Music.

Pinkham, Daniel (Composer). (1958). Christmas Cantata (Sinfonia Sacra) for Chorus and Double Brass Choir [Sheet music]. Paris: Alphonse leDuc Editions Musicales.

Scott, K. Lee (Composer). (2011.) Gloria [Sheet music]. St. Louis: MorningStar Music Publishers, Inc.

Vaughn Williams, R. (Composer). (1956.) A Choral Flourish [Sheet music]. London: Oxford University Press.